Early 2015-16 Winter Forecast Detailed Analysis

In the conclusion of my regional breakdown of the 2015-16 winter forecast last Sunday, I included a few winters that could be similar to this upcoming winter: 1957-58, 1986-87, and 2002-03. The 1957-58 and 1986-87 years are close ones to watch, even though there are still some pretty noticeable differences compared to this year. In recent months, you have likely heard about how this El Nino is going to be the strongest ever, and how it may end up smashing the previous records, even beating out the 1982-83 and 1997-98 El Ninos. My goal is not to try to dispute that in this forecast, although I do believe that forecast models are overestimating how strong this El Nino will ultimately become.

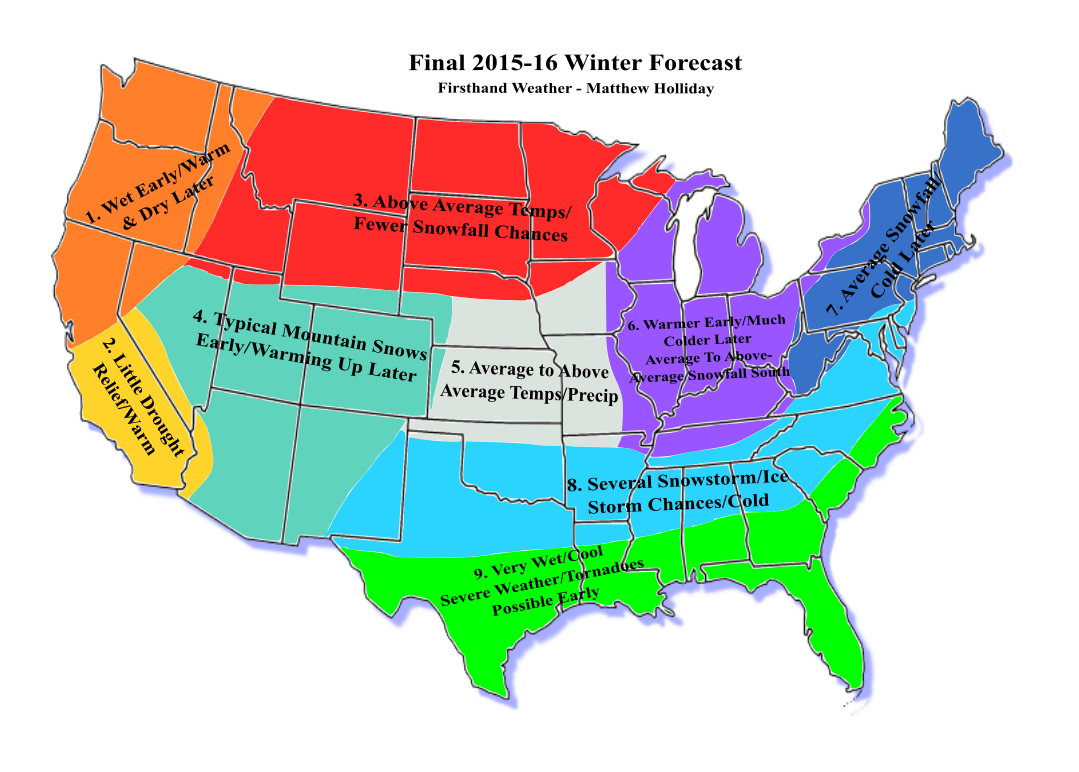

By the way, if you care nothing about the reasoning behind my winter forecast, but instead just want to know what to expect this winter (without all of the complicated details), then check out my region-by-region breakdown of the winter forecast by clicking here. You can consider this latest article “part 2” of my early 2015-16 winter forecast.

El Nino’s Come In Different Flavors/The Pacific Remains Very Warm:

I expressed on social media, my newsletter and on the website how and why this winter is going to be more difficult to pin down compared to the previous two winters. I also have warned and will continue to warn that one can’t simply combine all of the previous strong El Nino winters together and expect to get the same carbon-copy winter in 2015-16. While I’m predicting a moderate to strong El Nino winter this year, let’s not forget about the wrong El Nino forecasts in the past with the most recent misses being last year and in 2012. El Nino isn’t the only kid on the block, and I really don’t think that I can express that enough.

Based on what we have been able to observe in the past, sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies across the tropical Pacific can have a big influence on mid-latitude precipitation/temperatures. In fact, SST anomalies across the equatorial Pacific can also have a strong influence on heights/SST anomalies over other parts of the Pacific, influencing downstream weather in the U.S. During the 2013 summer, anomalously warmer waters began to emerge in the northeast Pacific, which have remained in place over the last two years. I’m not going to get into all of the research that has been done over the past couple of years that shows the connection between western equatorial Pacific warmth and how it can drive higher heights/warmer SST anomalies up the western U.S. coast into the Gulf of Alaska. What I want to mainly focus on for the moment is how these past two winters were driven by this warmth, despite the absence of any Greenland/Arctic blocking, and how this warmth may once again have an impact on the long-wave pattern over the U.S. this winter. If you want to do any further research on all of this, look up the North Pacific Mode, which is not the same as the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO).

As most are well aware, the last two winters have been extreme with very warm and dry conditions in the western U.S. and extreme cold and snowy/icy conditions in many locations across the central and eastern U.S. The biggest difference last winter was that the ridge was farther east, which pushed the trough farther east. On a smaller scale, that made a pretty sizable difference for some locations, but on a larger-scale, the past two winters were carbon-copies of one another. This shows the the very warm waters in the Gulf of Alaska enhanced ridging up over Alaska and along the West Coast, which forced a trough downstream. To put this is very simple terms, the jet stream pattern was very wavy.

2013-14 Winter:

2014-15 Winter (the eastern trough doesn’t look as pronounced because December 2014 was mild overall):

You hear a lot of talk about what the “typical” El Nino winter is like, and it makes me cringe every time I see a blog or someone on television talking about that. 1) There simply aren’t enough strong El Nino events to go off of. It’s not like we’ve had dozens of very strong El Nino winters in the past 50 years. You have the 1982-83 and 1997-98 very strong El Nino winters, and from a scientific standpoint, it’s never wise to go off a couple of seasons like that. There just aren’t enough to compare to. Of course, there are other strong El Nino winters, but even some of those don’t fit the stereotypical El Nino winter. 2) El Ninos come in different flavors. You heard me talk a lot last winter about how the exact placement of warmer waters along the equatorial Pacific plays a huge role in the overall pattern during a U.S. winter.

Comparing Two Sets Of Winters:

I want to show you a comparison just to give you an idea of how a more expansive warm pool over the northeast Pacific and down the West Coast can influence the pattern over the U.S. even during El Nino winters. Now keep in mind that it’s common to have a warm PDO during an El Nino winter, but the placement of this warmth is important.

Let’s begin with the 1972-73, 1982-83, 1997-98 winters. These are the big El Nino winters that everybody focuses on. I’ve combined all 3 winters to show you a SST anomaly map, a 500 mb height anomaly map, and a temperature anomaly map. Notice the much lower heights over the Gulf of Alaska that extend down into the southern U.S. Higher heights are over the northern U.S. This is the kind of setup you’d expect, given how far east the north-central Pacific cooler waters extend. Combine that with an east-based El Nino, and you get a very wet and cool south and a warmer and drier north. It’s cooler in the South because of more clouds and precipitation, not because of any connection to Arctic air getting displaced south.

Now let’s compare that to the 1957-58, 1986-87, 2002-03 winters. All of these were El Ninos, one strong and two moderate. Notice how expansive the warmth is in the northeast Pacific and how that warmth expands along the West Coast. The north-central cool pool doesn’t extend nearly as far east. In response, the Gulf of Alaska trough is farther west, a ridge extends farther west into western Canada and Alaska, and a more pronounced trough is over the the eastern third of the U.S. However, it’s important to note that I have noticed that more blocking over Greenland can actually flatten the ridge farther west over the West Coast and Alaska, which is why I encourage you to study these three winters individually.

By comparing these two sets of winters against one other, you get two different results. The first set favors cooler conditions over the Southwestern U.S. and a core of above average temperatures from the Northern Plains to the Northeast. The second set is completely different. The core of the coldest temperatures are across the Southeast, and it isn’t nearly as warm across the Northeast. The warmth extends from the western U.S. into the Northern Plains. It’s important to keep in mind that the placement of the SST anomalies across the equatorial Pacific and the state of the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)/Arctic Oscillation (AO) also played a role in the overall outcome of some of these winters, but it’s also important to realize that the configuration of the SST anomalies in the north-central and northeast Pacific can play a significant role in the overall pattern across the U.S.

For the record, I do believe that we will begin to see the warm pool in the northeastern Pacific break down some from the west especially this fall. This should get things looking a bit more similar to the 1957-58, 1986-87, and 2002-03 winters. If it doesn’t begin to break down at all, then I’ll honestly be able to say that something is occurring that we haven’t seen in modern history. It will also be important to monitor the future evolution of this El Nino, and the placement of the warmest waters across the equatorial Pacific. This El Nino could also begin to weaken sooner than normal since it began strengthening earlier than normal.

The Atlantic’s Influence:

The majority of you probably remember the epic winter of 2009-10, often referred to as “snowmageddon.” There were places getting snow that hadn’t seen snow in years, and the East Coast continuously got slammed with storm after storm. This was the perfect combination of having a moderate (borderline strong) El Nino event combined with a very negative NAO/AO through a good part of the winter. When you get strong blocking over Greenland, cold air gets displaced much farther to the south, and winter storms tend to ride up the entire East Coast. Because of our lack of a negative NAO/AO over the last two winters, that is one of the aspects of winter that has been somewhat absent.

It’s important for me to point out that predicting the future state of the NAO/AO is very difficult in advance, but the SST anomalies seem pretty unfavorable to have extensive blocking over Greenland this upcoming winter. In 2009-10, the waters were much warmer around Greenland, cooler across the central Atlantic, and warmer in the main development region (MDR) of the Atlantic. Right now, it’s the exact opposite. That doesn’t mean that there won’t be blocking, given that there are other factors (some that are unknown) that can influence the state of the NAO/AO, but I really have nothing to go off of. The 1986-87 winter is a good example of a winter with a negative NAO/AO with unfavorable sea surface temperature anomalies. I’ll be interested to see how the changes that we’re seeing in the Atlantic influence the overall pattern, and if we end up with another less “blocky” winter over that region.

2009 Winter vs. Current SST Anomalies:

As I began pointing out in 2013, you don’t need extensive blocking over Greenland and the Arctic to have a cold and snowy/icy winters in parts of the central and eastern U.S. We’ve had two winters that have been driven by warming in the northeast Pacific. Had those anomalously warmer waters not been present, I believe the previous two winters would have been rather boring and the exact opposite winter would have occurred.

Putting All Of This Together:

As you can tell, forecasting this upcoming winter is going to be complicated, but I really hope that I’ve given you enough info to do your own research, if you choose to do so. I still believe that the 1957-58, 1986-87, and 2002-03 winters are excellent years to study up on. If you choose to research this further, you’ll quickly notice that there are some key differences in each of those years, but that’s not a bad thing. Some had more Greenland/Arctic blocking than others, and one, in particular, was strongly influenced by warmer waters in the Gulf of Alaska and along the West Coast. What all of those years have in common is that there was a pronounced warm pool that extended from the northeast Pacific, down the West Coast, to the equatorial Pacific.

The reason SST anomalies are particularly important during the winter months is because as most already know, water has a higher heat capacity than land; therefore it takes much longer to change sea surface temperatures than land temperatures. These warmer or cooler bodies of water can warm or cool the air above them, which can have major impacts on weather patterns around the globe. That’s why the future evolution of the Pacific over these next few months is VERY important!

Hopefully this gives a little bit more of my reasoning behind why some aspects of my winter forecast differs than what would be expected from a typical strong El Nino winter. I explained a lot of what I was expecting this winter in my region-by-region breakdown of this forecast, which I strongly encourage you to read if you missed it. However, I want to briefly elaborate on a few points that I may have not been clear on last Sunday.

I’m expecting a very active winter in the wintry battle zone (region 7) of my forecast. With the combination of sub-tropical moisture getting pulled into the Southeast along with an active storm track, there should be plenty of opportunities to get wintry precipitation over that region if cold air is available (which in many cases, it should be). I explained last week that some of the most historic winter storms across the Southern Plains, Southeast, and Mid-Atlantic have occurred when temperatures as a whole for that winter were marginal. People automatically associate very cold weather with a lot of snow, but it doesn’t always work out that way.

I feel that a lot of the regions in my wintry battle zone will end up with above average snowfall, especially given that it only takes one storm to go above that average. However, I believe that ice storms could be a big issue this upcoming winter especially in the southern regions of my wintry battle zone, including cities like Birmingham, Atlanta, and maybe even Columbia. If sufficient cold air is available and the storm track is suppressed particularly far to the south, that threat could even be farther south, spilling into region 8 of my forecast. It’s really difficult to know exact details this far out though.

My region 6 area is the big wildcard this winter. I feel that a lot of those areas could definitely experience below average temperatures this winter, but determining how snowy this season will be for that region will be difficult at this point. There’s a reason that I cut off my wintry battle zone before reaching up the entire East Coast. The big bull’s eye should be a bit farther south this year, and cities like Boston shouldn’t get anything close to the amounts of snow that they got last winter. But if you’re located from Dallas, TX/OKC though the Southeast into parts of the Mid-Atlantic (my wintry battle zone), you’re the area I’m watching most closely at this point for a very active winter. Of course, that’s subject to change.

It seems to just be expected that California will get copious amounts of rain/snow this winter because of El Nino, and while I am predicting it to be much wetter over the area this winter, that is not guaranteed. When I get time, I plan to write a very detailed discussion on this topic. This El Nino should be strong enough to override the effects of any other potential negators in that area, but you just have to be careful when making those assumptions. I can give you examples of when it wasn’t wet during El Nino winters (e.g. 1986-87 winter) or when the heavier precipitation fell over northern California into Oregon instead of southern California (e.g. 1957-58, 2002-03 winters). You know my forecast, but believe with caution.

Right now, I’m leaning towards December being warmer for much of the U.S. with the exception maybe being over sections of the southern U.S. January, February, and even parts of March could be quite active and cold, particularly over the eastern U.S. I’ll be getting into details on specific months in my final winter forecast in November, so I’ll save that for when I hopefully have a much better handle on everything.

If you read this entire forecast, I’m impressed. In fact, if you made it through this entire forecast, comment on the site or on one of the social media pages, and let me know!